TRACCE no. 6 – by Jane Kolber

Scale drawings of the Vale de Vermelhosa Engravings.

The Etched in Time Project invited me to be a participant in recording the engravings in the Vale de Vermelhosa (Côa Valley Area, Portugal).

Special Côa

Location sketch of the Vale de Vermelhosa engraving site as seen from the southeast side of the valley

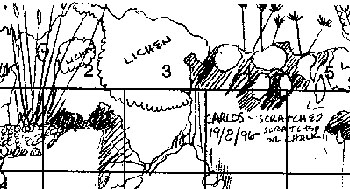

Recording features on a general sketch: grid, vegetation and surface characteristics

My task was to do site and scale drawings, which are techniques I frequently use in my recording projects in the southwestern United States (Figure 1).

The project began in the Vale de Vermelhosa where extremely fine lines were engraved into the schist rock surfaces and completely repatiniated. Light greatly affected their visibility leaving only short periods of time for intense scutiny. They are the most delicately drawn petroglyphs I have ever seen. Some of the figures had cracks dividing them indicating that the cracks had occured after their creation. It was necessary to work with utmost care and patience. The images are so old and finely executed that I found a need to treat them with great respect.

Belinha Campos, who wrote an article in the last issue of “Tracce” and Mafalda Borges CoeIho, both experienced Portuguese recorders and I applied drawing methods to the panels. We first developed forms based on those I use in this country. Drawings ranged from one of the entire area to individual close-ups of the elements. An overview was made of the north side of the valley where the engraved boulders were located. This included relative distances between boulders, vegetation, rock walls used in agriculture, indications of the glyph bearing rocks and an insert showing the location of the drawing in the overall landscape. This was done with no scale and only approximated the relative positions of the objects in the area. A similar photograph would provide the same information, but also include some distracting features that were left out of the drawing.

Overviews of the individual boulders were drawn next, including the shape, a bit of the surrounding vegetation and the approximate placement of the figures and lines. For these we included measurements of the entire engraved face of the boulder and the relative rock art positions on the surface.

Scale drawing of a portion of Panel 1. Each square equals 5

We then used the string grid technique developed by Lee and Bock to do scale drawings of portions of the panels.

Each boulder was divided up into one meter sections for which a schematic sketch was made. A one meter square string grid made of seine twine divided into ten centimeter squares was attached to the rock in areas where no rock art occurred with drafting tape which leaves no residue. The engraved lines were then drawn onto a sheet of paper bearing the same pattern of lines and squares. The engraved lines were drawn as close to the original as possible and never more than a few centimeters off. Sometimes lines were omitted if not visible.

This method is much more accurate when used on pecked petroglyphs and by those experienced in the method. Figures and lines with different degrees of patinas were drawn in different colors. However, problems arose when occasionally one continuous line was observed to be of different patinas. This was possibly caused by dust or mud being blown into lines. Reddish color alterations perhaps were caused by lichens or mineral seepage. Notes were made on the drawings to distinguish cracks, lichen, the Munsell soil color readings and any other factors noticed. Vandalism in the form of a name and date had occurred within a two week period when we were not there. This was also included for site management purposes.

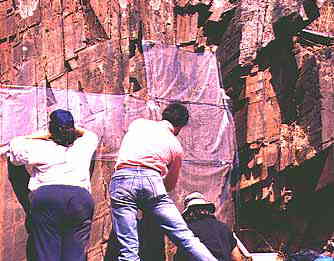

Transparency tracing on plastic sheets at Vermelhosa rock n. 1

Individual figures were drawn at a one to one ratio. For this a folding ruler was propped up in front of, but not touching, the element and a clear plastic ruler was used to find exact locations and lengths. Often much observation time was needed. The layering of the schist, the cracks and the environmental scratches all confused the eye.

At the second session, two Italian researchers, Andrea Arcà and Angelo Fossati proceeded with their tracing methods. The benefits of their method were reported on in the last issue of “Tracce.” They attached pieces of crystal plastic to the rock surface with Blu-Tack. Black permanent markers were used to duplicate each mark. Red was used to indicate the natural cracks.

This method produced accurate replicas of the engravings without necessitating much skill in drawing. I was pleased to have the opportunity to try this method.

I found some problems in using this method:

- The plastic slid around from place to place.

- The necessary hands positions became tiring quickly.

- The hand and plastic cast shadows on the work making visibility difficult

- It was difficult to keep hands steady and keep the flow of long lines.

- The pen marks were too thick.

- The Blu-Tak left a residue on the rock surface.

- The plastic stretches and shrinks with the temperature. When a tracing was placed over the measured scale drawing of the same element, the tracing was found to be too long. This was attributed to the stretching of the plastic.

A multiplexity of recording techniques insure a more accurate and complete documentation of a rock art site.

Scale drawings provide immediate images and impressions of a site and its components. They are completely non-intrusive. In recording very delicate images, they take much longer to complete and accuracy is not exact. Tracings can provide an exact rendering depending on the skill of the implementor and the weather and lighting conditions. The plastic is often difficult to handle, needs to be copied and reduced to be clearly observed and utilized. Storage concerns are a further problem. There is a possiblity that tracing may have some damaging affects on the rock images since it is mildly intrusive. Each recorder develops preferences for different processes. Each site requires suitably adapted methods. This project combined and experimented with the various methods in order to obtain as full an account as possible within the constraints of the situation.

Rock art recording is in its infancy. Only recently has its value been acknowledged. Experimentation will be ongoing for better and more efficient techniques.

Opposing and complementary methods must be acknowledged and studied in order to foster improvement. Our main concern is that we protect this precious world heritage and acknowledge that recording is a primary step in order to accomplish this goal.

Gravado no Tempo research team

Leave a Reply